Prof. Robert Kosara’s visualization tool, Parallel Sets (Parsets) fascinates me. If you download it and play with the sample datasets, you will likely be fascinated as well. It shows aggregations of categorical data in an interactive way.

I am so enamored with this tool, in particular, because it hits the sweet spot between beauty and utility. I’m a real fan of abstract and performance art. I love crazy paintings, sculptures and whatnot that force you to question their very existence. This is art that walks the line between brilliant and senseless.

When I look at the visualizations by Parsets, I’m inclined to print them off and stick them on my cube wall just because they’re “purty.” However, they are also quite utilitarian as every visualization should be. I’m going to show you how by using an example set of defects. Linda Wilkinson’s post last week was the inspiration for this. You can get some of the metrics she talks about in her post with this tool.

For my example, I created a dataset for a fictitious system under test (SUT). The SUT has defects broken down by operating system (Mac or Windows), who reported them (client or QA) and which part of the system they affect (UI, JRE, Database, Http, Xerces, SOAP).

Keeping in mind that I faked this data, here is the format:

DefectID,Reported By,OS,Application Component

Defect1,QA,MacOSX,SOAP

Defect2,Client,Windows,UI

Defect3,Client,MacOSX,Database

The import process is pretty simple. I click a button, choose my csv file, it’s imported. More info on the operation of Parsets is here. A warning: I did have to revert back to version 2.0. Maybe Prof. Kosara could be convinced to allow downloads of 2.0.

I had to check and recheck the boxes on the left to get the data into the order I wanted. Here is what I got:

So who wants to show me their piechart that they think is perfectly capable of showing this??? Oh wait, PIE CHARTS WON’T DO THIS. Pie Charts can only show you one variable. This one has 4.

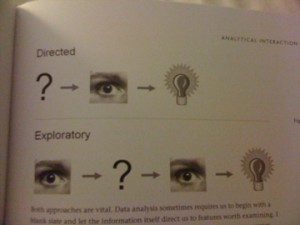

This is very similar to the parallel coordinate plot described by Stephen Few in Now You See It and shows Wilkinson’s example of analyzing who has reported defects. She was showing how to calculate a percentage for defects. See how the QA at the top is highlighted? There’s your percentage. Aside from who has reported the defects, Parsets makes it incredibly easy to see which OS has more defects and how the defects are spread out among the components. If I had more time, I would add a severity level to each defect. Wouldn’t that tell a story.

Parallel Sets is highly interactive. I can reorder the categories by checking and unchecking boxes. I can remove a category by unchecking a box if I wish.

By moving the mouse around, I can highlight and trace data points. Here I see that Defect 205 is a database defect for Mac OS X. Although I didn’t do it here, I bet that I could merge the Defect ID with a Defect Description and see both in the mouse over.

Parallel Sets is still pretty young, but is just so promising. I’m hoping that eventually, it will be viewable in a browser and easier to share. Visualizations like this one keep me engaged while providing me with useful information for exploratory analysis. That’s the promise of data viz, and Parallel Sets delivers.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=a455cc98-2fba-4096-b463-f155187ce3ac)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=ae7fa8d8-583d-4320-a177-75aa39da53f0)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=f7bd0376-c121-4b8d-ab73-2e24462060f6)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=e410f08a-f8ec-4d2c-958b-139a1056f149)

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=1613237b-ca73-4f07-89f0-18b524e87475)